I knew Aldous Huxley personally only after his so-called 'mystical period' had begun, and had not by then read much of his earlier work save the Point Counter Point and Chrome Yellow period. I encountered him first through Ends and Means, Brave New World, and then Grey Eminence.

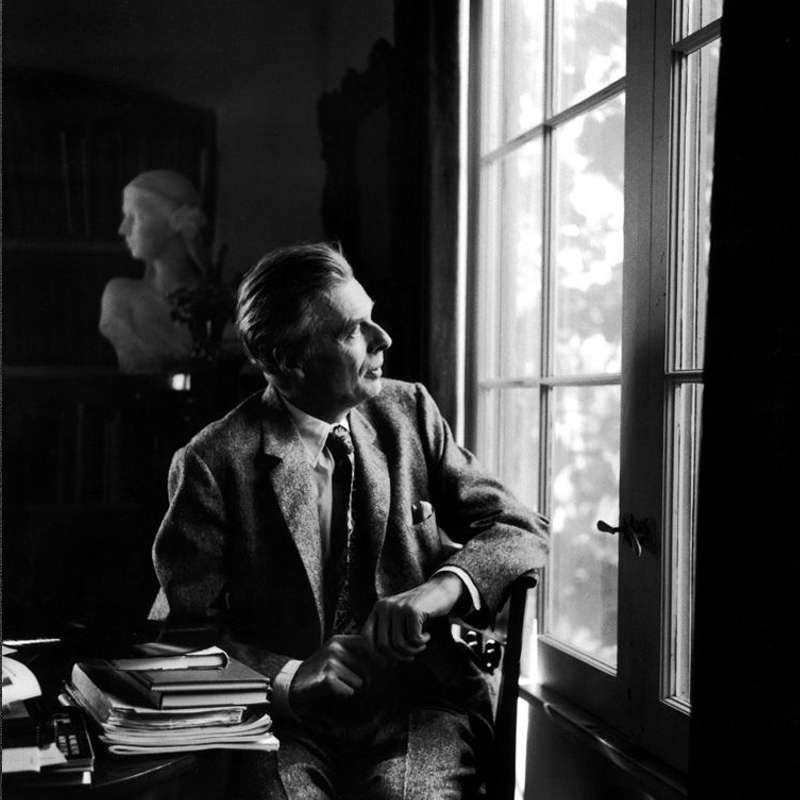

It was just after he had written the latter that I got in touch with him for the first time, and was wholly enchanted by the breadth and intricacy of his interests. He was a marvelous conversationalist. Every time I met him I felt charged in some way, as if a whole new world of ideas had been opened up to me. He was an entrancing talker. I well remember the day when we were having lunch at the Tokyo Restaurant in San Francisco, and his conversation reduced everyone at the neighboring tables to silence because they wanted to listen in.

When I first knew Aldous Huxley, he was in the beginning of the period in which he became interested in mystical experience and the transformation of consciousness. At that time I felt that he was following a type of mystical philosophy that rejected the material universe as a degraded mode of consciousness.

It was about then that D.S. Savage wrote a critique of Huxley’s work, in the Sewanee Review, saying that the old Huxley and the new Huxley were really just the same. Don't, he said, be deceived by the change. The old Huxley in Point Counter Point is a bitter and cynical man of destructive brilliance; he loves to pick people apart. But this is the same Huxley appearing now in the guise of a mystic, for in Eastern mysticism the object is to transcend and thus abolish personality and all differentiation. "The ideal of dissolving the whole world of multiplicity and of form into a sort of undifferentiated morass is a new way of playing Huxley’s old game."

There was, as I also felt, some truth in this at the time, but obviously Savage didn’t know Huxley very well as a person. What was so striking about the man and his surroundings — the kind of house he lived in and the works of art he collected — was his actual fascination with the material world and his love of the good life. Huxley's prickly attitude, his critical-satirical point of view, was not really destructive: It was a defense of his own sensitivity. He was a very sensitive man indeed—too sensitive. Therefore he adopted a slightly aloof and superior attitude. After all, he and I went through the same kind of education—the British 'public school' [meaning, oddly, 'private school' in American terms] — and thus I understand not only his sexual preoccupations (as they come out in The Genius and the Goddess) but also the need for just this kind of 'character armor.'

As the years passed — say from 1943 on — Aldous Huxley's philosophy made a definite progression. He became, in effect, a full-fledged Mahayana Buddhist, with the vision of the total union of the spiritual and physical domains. This is the Bodhisattva ideal, not of passing out of the world of form into the formless world of Nirvana, but of realizing the inner unity of Nirvana and the everyday world.

Huxley saw this Buddhist unity not as one who, like a laissez-faire do-nothing reactionary, would leave the world as it is, but as one who incarnated the paradox that if you can see that the everyday world, as it is, is a divine manifestation, then and then only can you love it enough to want to change it in a constructive way. Otherwise people are changing the world not because they love it but because it is personally inconvenient to them.

This philosophy of spiritual-materialism found its final expression in Island, a book with which I find myself in complete harmony, so far as its Philosophical content is concerned. Huxley made it a novel because the novelist was so largely his role and because the book had to be a counterpart to Brave New World.

As a writer of fiction, Huxley’s skill in describing the ideal was not up to his skill in satirizing the real. Yet it must be admitted that for any artist the depiction of heaven is the hardest task of all—and thus the task in which he may most easily make a fool of himself.

Island is a thinly-fictionalized collection of essays on education, psychology, and metaphysics in which Huxley stuck out his neck as far as it would go. He advocated everything calculated to evoke the ridicule of sensible people — abolition of the sacred American family; free love; Tantric sex practices; drugs for inducing mystical experience, and the fantasy of the island paradise. He made himself a sitting duck for snickers in the literary reviews and scandal in the Sunday papers.

But Huxley was no fool, and no sentimentalist. It is just in those sore-point areas where the public defends itself by jeers without argument, that we find the most touchy and important issues of the time. Within twenty years it will be clear to all of us that Aldous Huxley had a genius for raising the right questions.

*Autumn, 1947. Reprinted in B. Rajan, ed., The Novelist as Thinker, London: Dobson, 1948, OLZ