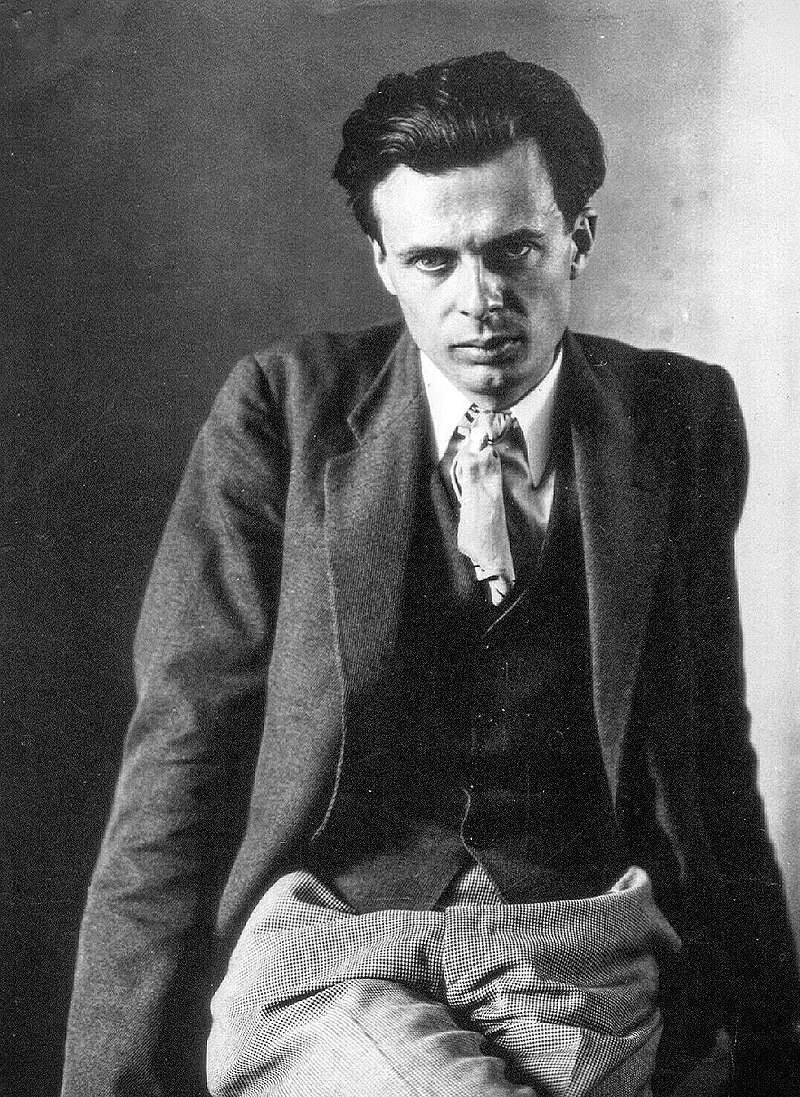

Aldous Huxley died of cancer on the same day that John Kennedy was assassinated. The violent death of the young statesman overshadowed the peaceful departure of the old philosopher. The public and the press have taken scant notice of his passing. Since Huxley devoted much attention and interest to the field of psychedelic research (he wrote three books and many articles on the subject), it is fitting that we should dedicate this issue of The Psychedelic Review to his memory. For this reason we have invited four men, who knew Huxley personally, to contribute their thoughts on the departure of this illuminated soul.

The choice is always ours.

Then, let me choose the longest art,

the hard Promethean way

Cherishingly to tend and feed and fan

That inward fire, whose small precarious flame,

Kindled or quenched, creates

The noble or the ignoble men we are,

The worlds we live in and the very fates,

Our bright or muddy star,

—Aldous Huxley (from Orion)

Huxley was the last of a rare and transitory species that appeared briefly in the ultimate phase of Renaissance Man: The scholar of style; the essayist of genius; the ultra-learned novelist who galvanizes his characters with the high charge of his strange knowledge and the crackling static of his wit; the amazingly informed amateur whose selfless desire for all information, and impartial love of any understanding, kept him perpetually seeking for insights in the sciences and the humanities, in the ancient esoteric tradition of mysticism and in the temerarious, empirical practices of the latest, most heterodox therapies.

Here was the rarest of alloys. Taste combined with temerity, daring speculation delivered in a perfect rendition of lucid and elegant restraint.

This blend of opposites gave to Aldous Huxley’s mind a temper that was perhaps hard. unique It is certainly to imagine that an intellect of this extraordinary, idiosyncratic cast will again emerge. For now has ended that brief climate of thought in which so rare a species could appear, let alone so advanced a specimen flower.

This eulogy will be uttering empty if, in taking farewell, we do not say: We shall not look upon his like again.

When Aldous Huxley was at M.I.T. in the fall of 1960, giving lectures which drew listeners so heavily that they jammed traffic all the way across the Charles River into Boston, I once spoke of those crowds as a tribute. “It’s because I’ve been around so long,” he replied. “I’ve become like Queen Anne’s Cottage. If I live to be a hundred I shall be like Stonehenge.”

He didn’t live to be a hundred, and the world is the loser. Most obviously, it has lost an encyclopedic intelligence. That adjective is overworked these days, but in his case it comes close to being exact. Indeed, when a leading journal felt that an encyclopedia — the Fourteenth Edition of the Britannica — itself needed to be brought under review, no one was surprised when Huxley was asked to do the job.

More impressive than the range of the man’s mind, however, was its sympathy and interest. Few major intelligences since William James have been as open. Huxley’s regard for mysticism was well known by dint of being so nearly notorious. What some overlooked was his equal interest in the workaday world and its exigencies: peace, the population explosion, and conservation of our natural resources.

To those who, greedy for transcendence, deprecated the mundane he counseled that, “we must make the best of both worlds.” To their opposites, the positivists, his word was, “All right, one world at a time; but not half a world !”

Accepting the fact that “truth lies at the bottom of a very muddy well,” he descended: to ESP and LSD, to ‘sight without glasses’ and Vedanta. But never as martyred hero; there wasn’t a grain of Invictus in him. If he lost his reputation, it was not for his omnivorous interests but because he wasn't content simply to do what he could do well, His competence bored him.

So the master of words moved on to what eludes them, remarking over his shoulder that “language is a device for taking the mystery out of reality.” Not needing triumph or adulation, he could bypass them for truth.

He could because he had so little egoism. A supreme unpretentiousness characterized him to the end. “It’s a bit embarrassing,” he said, “to have been concerned with the human problem all one’s life and find at the end that one has no more to offer by way of advice than “Try to be a little kinder.”

If, as he had earlier remarked, the central technique for man to learn is “the art of obtaining freedom from the fundamental human disability of egoism,” Huxley achieved that freedom.

But this wasn’t his supreme achievement, for his personal problem was never pride so much as pessimism — “tomorrow, and tomorrow, and tomorrow, creeps in this pretty pace from day to day." His final victory, therefore, lay not in emerging selfless but in winning through to equanimity, to evenness of spirit and a generalized good-cheer. Thereby the line he used to close his best novel becomes the appropriate epitaph for his own life-story: “Of such is the Kingdom of Heaven.” Said this time without sarcasm.