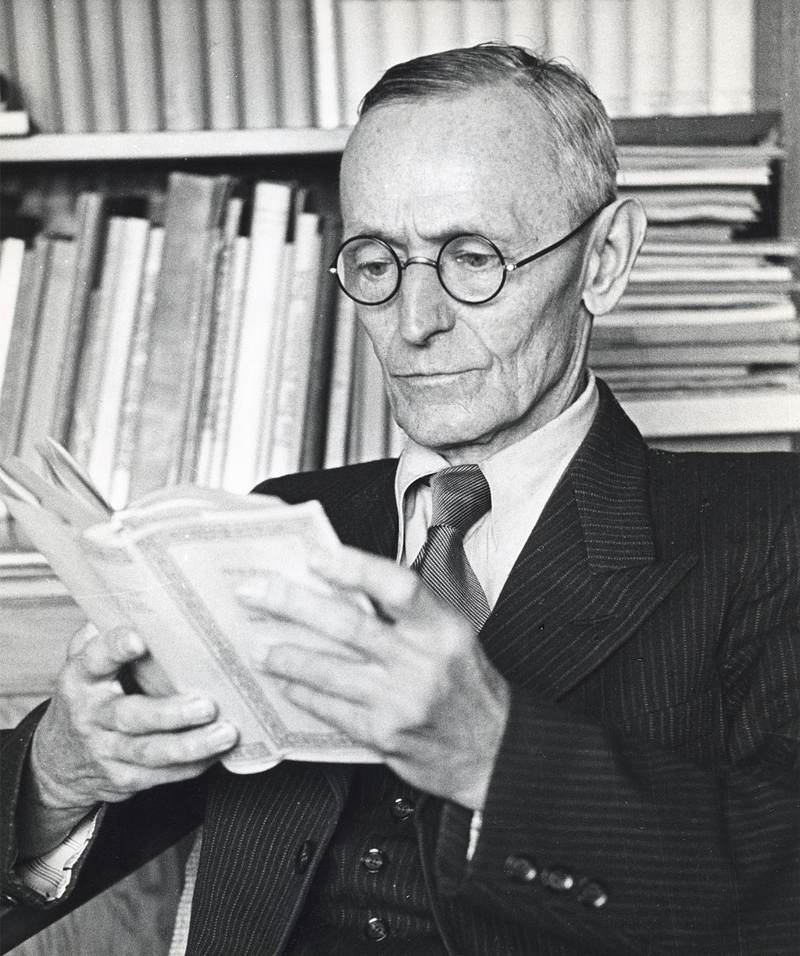

Herman Hesse was born in July, 1877, in the little Swabian town of Calw, the son of Protestant missionaries. His home background and education were pietistic, intellectual, classical. He entered a theological seminary at the age of fourteen with the intention of taking orders, and left two years later.

In Basel he learned the book trade and made his living as a bookseller and editor of classical German literary texts. He became acquainted with Jacob Burckhardt, the great Swiss historian and philosopher, who later served as the model for the portrait of Father Jacobus in The Bead Game In 1914, Hesse’s “unpatriotic” anti-war attitude brought him official censure and newspaper attacks.

Two months after the outbreak of the war, an essay entitled O Freunde, nicht diese Tone (O Friends, not these tones) was published in the Neue Zürcher Zeitung. It was an appeal to the youth of Germany, deploring the stampede to disaster.

In 1911 he travelled in India. From 1914 to 1919 he lived in Bern, working in the German embassy as an assistant for prisoners of war.

A series of personal crises accompanied the external crisis of the war: his father died; his youngest son fell seriously ill; his wife suffered a nervous breakdown and was hospitalized. In 1919, the year of the publication of Demian, Hesse moved to the small village of Montagnola by the lake of Lugano and remained there till the end of his life.

In 1923 Hesse acquired Swiss citizenship, and in 1927 re-married. He steeped himself in Indian and Chinese literature and philosophy. The latter particularly through the masterful translations of Chinese texts by Richard Wilhelm.

In 1931, he remarried a third time and moved to another house in Montagnola which had been provided for him by his friend, H. C. Bodmer.

In 1946 he was awarded the Nobel Prize.

In 1962, at the age of 85, he died. Asked once what were the most important influences in his life, he said they were: “the Christian and completely non-nationalist spirit of my parents’ home,” the “reading of the great Chinese masters,” and the figure of the historian Jacob Burckhardt.

Few writers have chronicled with such dispassionate lucidity and fearless honesty the progress of the soul through the stages of life. Peter Camenzind (1904); Demian (1919); Siddhartha (1922); Steppenwolf (1927); Narziss und Goldmund (1930); Journey to the East (1932) Magister Ludi (1943)—different versions of spiritual autobiography, different maps of the interior path. Each new step revises the picture of all the previous steps, each experience opens up new worlds of discovery in a constant effort to communicate the vision.

As John Cage is fond of reminding us, writing is one thing and reading is another. All writings, all authors, are thoroughly misunderstood. Most wise men do not write because they know this. The wise man has penetrated through the verbal curtain, seen and known and felt the life-process. We owe him our gratitude when he remains with us and tries to induce us to share the joy.

The great writer is the wise man who feels compelled to translate the message into words. The message is, of course, around us and in us at all moments. Everything is a clue. Everything contains all the message. To pass it on in symbols is unnecessary but perhaps the greatest performance of man.

Wise men write (with deliberation) in the esoteric. It’s the way of making a rose or a baby. The esoteric form is maya, the hallucinatory facade. The meaning is within. The greatness of a great book lies in the esoteric, the seed meaning concealed behind the net of symbols. All great writers write the same book, changing only the exoteric trappings of their time and tribe.

Hermann Hesse is one of the great writers of our time. He wrote Finnegan’s Wake in several German versions. In addition to being a wise man, he could manipulate words well enough to win the Nobel Prize.

Most readers miss the message of Hesse. Entranced by the pretty dance of plot and theme, they overlook the seed message. Hesse is a trickster. Like nature in April, he dresses up his code in fancy plumage. The literary reader picks the fruit, eats quickly, and tosses the core to the ground. But the seed, the electrical message, the code is in the core.

p>Take Siddhartha[1]—the primer for young Bodhisattvas, written when Hesse was forty-five. Watch the old magician warming up to his work. We are introduced to a proud young man, strong, handsome, supple-limbed, graceful. Siddhartha is young and ambitious. He seeks to attain the greatest prize of all—enlightenment. Cosmic one-upmanship. He masters each of the other-worldly games. The Vedas. Asceticism. Matches his wits against the Buddha himself. Tantric worldly success.“We find consolations, we learn tricks with which we deceive ourselves, but the essential thing—the way—we do not find.” “Wisdom is not communicable.” “I can love a stone, Govinda, and a tree or a piece of bark. These are things and one can love things. But one cannot love words... Nirvana is not a thing; there is only the word Nirvana.”

Then in the last pages of the book, Hermann Hesse, Nobel Prize novelist, uses words to describe the wonderful illumination of Govinda, who:

"...no longer saw the face of his friend Siddhartha. Instead he saw other faces, many faces, a long series, a continuous stream of faces—hundreds, thousands, which all came and disappeared and yet all seemed to be there at the same time, which all continually changed and renewed themselves and which were yet all Siddhartha."

He saw the face of a fish, of a carp, with tremendous painfully opened mouth, a dying fish with dimmed eyes. He saw the face of a newly born child, red and full of wrinkles, ready to cry. He saw the face of a murderer, saw him plunge a knife into the body of a man; at the same moment he saw this criminal kneeling down, bound, and his head—cut off by an executioner. He saw the naked bodies of men and women in the postures and transports of passionate love. He saw corpses stretched out, still, cold, empty. He saw the heads of animals, boars, crocodiles, elephants, oxen, birds. He saw Krishna and Agni.

He saw all these forms and faces in a thousand relationships to each other, all helping each other, loving, hating and destroying each other and become newly born. Each one was mortal, a passionate, painful example of all that is transitory.

Yet none of them died, they only changed, were always reborn, continually had a new face: only time stood between one face and another. And all these forms and faces rested, flowed, reproduced, swam past and merged into each other, and over them all there was continually something thin, unreal and yet existing, stretched across like thin glass or ice, like a transparent skin, shell, form or mask of water—and this mask was Siddhartha’s smiling face which Govinda touched with his lips at that moment.

Govinda saw that this mask-like smile, this smile of unity over the flowing forms, this smile of simultaneousness over the thousands of births and deaths—this smile of Siddhartha—was exactly the same as the calm, delicate, impenetrable, perhaps gracious, perhaps mocking, wise, thousand-fold smile of Gotama, the Buddha, as he had perceived it with awe a hundred times. It was in such a manner, Govinda knew, that the Perfect One smiled.

Those who have taken one of the psychedelic drugs may recognize Govinda’s vision as a classic LSD sequence. The direct visual confrontation with the unity of all men, the unity of life. That Hesse can write words such as ‘unity,’ ‘love,’ ‘Nirvana,’ is easily understood.

Every Hindu textbook gives you the jargon. But his description of the visual details of the cosmic vision, the retinal specifics, is more impressive. Whence came to Hesse these concrete sensations?

The similarity to the consciousness-expanding drug experience is startling. The specific, concrete ‘is-nes’ of the illuminated moment usually escapes the abstract philosopher of mysticism.

Did Hesse reach this visionary state himself? By meditation? Spontaneously? Did Herman Hesse the novelist himself use the chemical path to enlightenment?

The answer to these questions is suggested in the next lesson of the master : Steppenwolf—a novel of crisis, pain, conflict, torture—at least on the surface. Hesse writes in a letter:

“If my life were not a dangerous painful experiment, if I did not constantly skirt the abyss and feel the void under my feet, my life would have no meaning and I would not have been able to write anything.”

Most readers sophisticated in psychodynamics recognize the drama presented—the conflict between ego and id, between spirit and material civilization, the “wolfish, satanic instincts that lurk within even our civilized selves,” as the jacket of the paperback edition has it. “These readers [writes Hesse] have completely overlooked that above the Steppenwolf and his problematical life there exists a second, higher, timeless world... which contrasts the suffering of the Steppenwolf with a transpersonal and transtemporal world of faith, that the book certainly tells of pain and suffering but is the story of a believer not a tale of despair.”

As in Siddhartha, Hesse involves the reader in his fantastic tale, his ideas, his mental acrobatics, only to show at the end that the whole structure is illusory mind-play. The mental rug is suddenly pulled out from under the gullible psychodynamic reader.

This Zen trick is evident on at least two levels in the Steppenwolf. First, in the little ‘Treatise,’ a brilliant portrait of Harry, the man with two souls: the man—refined, clever and interesting; and the wolf—savage, untamable, dangerous and strong. The treatise describes his swings of mood, his bursts of creativity, his ambivalent relationship to the bourgeoisie, his fascination with suicide, his inability to reconcile the two conflicting selves. A breathtakingly subtle psychological analysis. Then, the sleight of hand:

"There is... a fundamental delusion to make clear. All interpretation, all psychology, all attempts to make things comprehensible, require the medium of theories, mythologies and lies; and a self-respecting author should... dissipate these lies so far as may be in his power..."

Harry consists of a hundred or a thousand selves, not of two. His life oscillates, as everyone’s does, not merely between two poles, such as the body and the spirit, the saint and the sinner, but between thousands. Man is an onion made up of a hundred integuments, a texture made up of many threads.

The ancient Asiatics knew this well enough, and in the Buddhist Yoga an exact technique was devised for unmasking the illusion of the personality. The human merry-go-round sees many changes: the illusion that cost India the efforts of thousands of years to unmask is the same illusion that the West has labored just as hard to maintain and strengthen.

The dualistic self-image is described—the fascinating and compelling Freudian metaphor—and is then exposed as a delusion, a limited, pitiful perspective, a mind-game.

The second example of this trick occurs at the end of the book. We have followed Hesse in his descriptions of Harry, as he runs through a series of vain attempts to conquer his despair—through alcohol, through sex, through music, through friendship with the exotic musician Pablo—finally he enters the Magic Theater. “Price of Admission, your Mind.”—In other words, a mind-loss experience.

"From a recess in the wall [Pablo] took three glasses and a quaint little bottle... He filled the three glasses from the bottle and taking three long thin yellow cigarettes from the box and a box of matches from the pocket of his silk jacket he gave us a light... Its effect was immeasurably enlivening and delightful—as though one were filled with gas and had no longer any gravity."

Pablo says:

"You were striving, were you not, for escape? You have a longing to forsake this world and its reality and to penetrate to a reality more native to you, to a world beyond time... You know, of course, where this other world lies hidden. It is the world of your own soul that you seek. Only within yourself exists that other reality for which you long... All I can give you is the opportunity, the impulse, the key. I help you to make your own world visible... This... theater has as many doors into as many boxes as you please, ten or a hundred or a thousand, and behind each door exactly what you seek awaits you...

You have no doubt guessed long since that the conquest of time and the escape from reality, or however else it may be that you choose to describe your longing, means simply the wish to be relieved of your so-called personality. That is the prison where you lie. And if you enter the theatre as you are, you would as everything through the eyes of Harry and the old spectacles of the Steppenwolf. You are therefore requested to lay these spectacles here in the cloak-room, where you will find it again when you wish. The pleasant dance from which you have just come, the treastise on the Steppenwolf, and the little stimulant that we have only just this morning partaken of may have sufficiently prepared you."

It seems clear that Hesse is describing a psychedelic experience, a drug-induced loss of self, a journey to the inner world. Each door in the Magic Theatre has a sign on it, indicating the endless possibilities of the experience. A sign called "Jolly Hunting. Great Automobile Hunt" indicates a fantastic orgy of mechanical destruction in which Harry becomes a lustful murderer. A second sign reads: "Guidance in the Building-Up of the Personality. Success Guaranteed,” which indicates a kind of chess game in which the pieces are the part of the personality. Cosmic psychotherapy.

“We demonstrate to anyone whose soul has fallen to pieces that he can rearrange these pieces of a previous self in what order he pleases, and so attain to an endless multiplicity of moves in the game of life.” Another sign reads: “All Girls Are Yours,” and carries Harry into inexhaustible sexual fantasies.

The crisis of the Steppenwolf, his inner conflicts, his despair, his morbidity and unsatisfied longing are dissolved in a whirling kaleidoscope of hallucinations:

“I knew that all the hundred thousand pieces of life’s game were in my pocket. A glimpse of its meaning had stirred my reason and I was determined to begin the game afresh. I would sample its tortures once more and shudder again at its senselessness. I would traverse not once more, but often, the hell of my inner being. One day I would be a better hand at the game. One day I would learn how to laugh. Pablo was waiting for me, and Mozart too.”

So Harry Haller, the Steppenwolf, had his psychedelic session, discovered instead of one reality, infinite realities within the brain. He is admitted into the select group of those who have passed through the verbal curtain into other modes of consciousness. He has joined the elite brotherhood of the illuminati.

And then what? Where do you go from there? How can the holy sense of unity and revelation be maintained? Does one sink back into the somnambulent world of rote passion, automated action, egocentricity? The poignant cry of ex-League member, Herman Hesse:

“That almost all of us—and also I, even I—should again lose myself in the soundless deserts of mapped out reality, just like officials and shop-assistants who, after a party or a Sunday outing, adapt themselves again to everyday business life!”

These are issues faced by everyone who has passed into a deep, trans-ego experience. How can we preserve the freshness; illuminate each second of subsequent life? How can we maintain the ecstatic oneness with others?

Throughout the ages mystical groups have formed to provide social structure and support for transcendence. The magic circle, often secret, always persecuted by the sleep-walking majority, these cults move quietly in the background shadows of history. The problem is, of course, the amount of structure surrounding the mystical spark. Too much, too soon, and you have priesthood ritual on your hands. And the flame is gone. Too little and the teaching function is lost, the interpersonal unity drifts into gaseous anarchy: The Bohemians. The Beats. The lonely arrogants.

Free from attachment to self, to social games, to anthropomorphic humanism, even to life itself, the illuminated soul can sustain the heightened charge of energy released by transcendent experiences. But such men are rare in any century. The rest of us seem to need support on the way. Men who attempt to pursue the psychedelic drug path on their own are underestimating the power and the scope of the nervous system.

A variety of LSD casualties results: breakdown, confusion, grandiosity, prima-donna individualism, disorganized eccentricity, sincere knavery and retreat to conformity. It makes no more sense to blame the drug for such casualties than it does to blame the nuclear process for the bomb. Would it not be more accurate to lament our primitive tribal pressures towards personal power, success, individualism?

Huston Smith has remarked that of the eight-fold path of the Buddha, the ninth and greatest is Right Association. The transpersonal group. The consciousness-expansion community. Surround yourself after the vision, after the psychedelic session, with friends who share the goal, who can uplevel you by example or unitive love; who can help reinstate the illumination.

The sociology of transcendence. Hesse takes up the problem of the transpersonal community in the form of the League of Eastern Wayfarers.[3]

”It was my destiny to join in a great experience. Having had the good fortune to belong to the League, I was permitted to be a participant in a unique journey.” The narrator, H.H., tells that the starting place of the journey was Germany, and the time shortly after World War I:

"...our people at that time were lured by many phantoms, but there were also many real spiritual advances. There were Bacchanalian dance societies and Anabaptist groups, there was one thing after another that seemed to point to what was wonderful and beyond the veil."

There were also scientific and artistic groups engaged in the exploration of consciousness-expanding drugs. Kurt Beringer's monograph, Der Meskalinrausch[4] describes some of the scientific experiments and the creative applications. René Daumal’s novel, Le Mont Analogue, is a symbolic account of a similar league journey in France. The participants were experimenting widely with drugs such as hashish, mescaline and carbon tetrachloride.

Hesse never explicitly names any drugs in his writings, but the passages quoted earlier from the Steppenwolf are fairly unequivocal in stating that some chemical was involved and that it had a rather direct relationship to the subsequent experience. Now, after this first enlightenment, in Journey to the East, H.H. tells of subsequent visits to the Magical Theatre.

"We not only wandered through Space, but also through time. We moved towards the East, but we also traveled into the Middle Ages and the Golden Age; we roamed through Italy or Switzerland, but at times we also spent the night in the 10th century and dwelt with the patriarchs or the fairies. During the times I remained alone, I often found again places and people of my own past. I wandered with my former betrothed along the edges of the forest of the Upper Rhine, caroused with friends of my youth in Tubingen, in Basle or in Florence, or I was a boy and went with my school-friends to catch butterflies or to watch an otter, or my company consisted of the beloved characters of my books; ... For our goal was not only the East, or rather the East was not only a country and something geographical, but it was the home and youth of the soul, it was everywhere and nowhere, it was the union of all times.

Later the link between the Steppenwolf’s drug liberation and the League becomes more specific:

"When something precious and irretrievable is lost, we have the feeling of having awakened from a dream. In my case this feeling is strangely correct, for my happiness did indeed arise from the same secret as the happiness in dreams; it arose from the freedom to experience everything imaginable simultaneously, to exchange outward and inward easily, to move Time and Space about like scenes in a theatre."

Hesse is always the esoteric hand, but there seems to be little doubt that beneath the surface of his Eastern allegory runs the history of a real-life psychedelic brotherhood. The visionary experiences described in Journey to the East are identified by location and name of participants. A recently published biography[6] traces the connections between these names and locations and Hesse’s friends and activities at the time.

"And again and again, in Swabia, at Bodensee, in Switzerland, everywhere, we met people who understood us, or were in some way thankful that we and our League and our Journey to the East existed. Amid the tramways and banks of Zürich, we came across Noah’s Ark guarded by several old dogs which all had the same name, and which were bravely guided across the dangerous depths of a calm period by Hans C., Noah’s descendant, friend of the arts."

Hans C. Bodmer is Hesse’s friend, to whom the book is dedicated, and who later bought the house in Montagnola for Hesse. He lived at the time in a house in Zürich named ‘The Ark.’

"One of the most beautiful experiences was the League’s celebration in Bremgarten; the magic circle surrounded us closely there. Received by Max and Tilli, the lords of the castle..."

Castle Bremgarten, near Bern, was the house of Max Wassmer, where Hesse was often a guest. The “Black King” in Winterthur refers to another friend, Georg Reinhart, to whose house, “filled with secrets,’ Hesse was often invited.

The names of artists and writers which occur in Journey to the East, are all either directly the names of actual historical persons or immediately derived from them: Lauscher, Klingsor, Paul Klee, Ninon (Hesse’s wife), Hugo Wolf, Brentano, Lindhorst, etc. In other words, it appears likely that the scenes described are based on the actual experiences of a very close group of friends who met in each other’s homes in Southern Germany and Switzerland and pursued the journey to what was “not only a country and something geographical, but it was the home and youth of the soul, it was everywhere and nowhere, it was the union of all times.”

So the clues suggest that for a moment in ‘historical reality’ a writer named Hermann Hesse and his friends wandered together through the limitless pageants of expanded consciousness, down through the evolutionary archives, Then, apparently, H.H. loses contact, slips back to his mind and his egocentric perspectives.

"...the pilgrimage had shattered... the magic had then vanished more and more.” He has stumbled out of the life-stream into robot rationality, H.H. wants to become an author, spin in words the story of his life. “I, in my simplicity, wanted to write the story of the League, I who could not decipher or understand one-thousandth part of these millions of scripts, books, pictures and references in the archives!" Archives! The cortical library?

What then was, is, the League? Is it the exoteric society with a golden-clad President, Leo, maker of ointments and herbal cures, and a Speaker, and a High Throne, and an extended council hall?

These are but the exoteric trappings. Is not the League rather the “procession of believers and disciples... incessantly... moving towards the East, towards the Home of Light”? The eternal stream of life ever unfolding. The unity of the evolutionary process, too easily fragmented and frozen by illusions of individuality. “...a very slow, smooth but continuous flowing or melting; ... It seemed that, in time, all the substance from one image would flow into another and only one would remain...”

Many who have made direct contact with the life-process through a psychedelic or spontaneous mystical experience find themselves yearning for a social structure. Some external form to do justice to transcendental experiences. Hermann Hesse again provides us with the esoteric instructions. Look within. The League is within. So is the two-billion-year-old historical archive, your brain. Play it out with those who will dance with you, but remember, the external differentiating forms are illusory. The union is internal. The League is in and around you at all times.

But to be human is to be rational. Homosapiens wants to know. Here is the ancient tension. To be. To know. Well, the magician has a spell to weave here, too. The intellect divorced from old-fashioned neurosis, freed from egocentricity, from semantic reification. The mind illuminated by meditation ready to play with the lawful rhythm of concepts. The Bead Game. (Magister Ludi),[7] begun in 1931, finished eleven years later, was published six months after its completion, but in Switzerland, not Germany.

“In opposition to the present world I had to show the realm of mind and of spirit, show it as real and unconquerable; thus my work became a Utopia, the image was projected into the future, and to my surprise the world of Castalia emerged almost by itself. Without my knowledge, it was already preformed in my soul.” Thus wrote Hesse in 1955.

The Bead Game is the synthesis and end-point of Hesse’s developing thought; all the strands begun in Siddhartha; Journey to the East; Steppenwolf are woven together into a vision of a future society of mystic game-players.

The “players with pearls of glass” are an elite group of mystics who, analogously to the monastic orders of the Middle Ages, have created a mountain retreat to preserve cultural and spiritual values. The core of their practice is the bead game, “a device that comprises the complete contents and values of our culture. The game consists in the manipulation of a complex archive of symbols and formulae, based in their structure on music and mathematics, by means of which all knowledge, science, art and culture can be represented.

"This Game of games... has developed into a kind of universal speech, through the medium of which the players are enabled to express values in lucid symbols and to place them in relation to each other... A Game can originate, for example, from a given astronomical configuration, a theme from a Bach fugue, a phrase of Leibnitz or from the Upanishads, and the fundamental idea awakened can, according to the intention and talent of the player, either proceed further and be built up or enriched through assonances to relative concepts. While a moderate beginner can, through these symbols, formulate parallels between a piece of classical music and the formula of a natural law, the adept and Master of the Game can lead the opening theme into the freedom of boundless combinations."

The old dream of a universitas, a synthesis of human knowledge, combining analysis and intuition, science and art, the play of the free intellect, governed by aesthetic and structural analogies, not by the demands of application and technology.

Again, on the intellectual plane, the problem is always just how much structure the mind game should have. If there are no overall goals or rules, we have ever-increasing specialization and dispersion, breakdown in communication, a Babel of cultures, multiple constrictions of the range in favor of deepening the specialized field. Psychology. If there is too much structure or over-investment in the game-goals, we have dogmatism, stifling conformity, ever-increasing triviality of concerns, adulation of sheer techniques, virtuosity at the expense of understanding: Psychoanalysis.

In the history of the bead game, the author explains, the practice of meditation was introduced by the League of Eastern Wayfarers in reaction against mere intellectual virtuosity. After each move in the game, a period of silent meditation was observed; the origins and meaning of the symbols involved were slowly absorbed by the players. Joesph Knecht, the Game Master, whose life is described in the book, sums up the game as follows:

"The Game, as I interpret it, encompasses the player at the conclusion of his meditation in the same way as the surface of a sphere encloses its centre, and leaves him with the feeling of having resolved the fortuitous and chaotic world into one that is symmetrical and harmonious."

Groups which attempt to apply psychedelic experiences to social living will find in the story of Castalia all the features and problems which such attempts inevitably encounter: the need for a new language or set of symbols to do justice to the incredible complexity and power of the human cerebral machinery; the central importance of maintaining direct contact with the regenerative forces of the life-process through meditation or other methods of altering consciousness: the crucial and essentially insoluble problem of the relation of the mystic community to the world at large.

Can the order remain an educative, spiritual force in the society, or must it degenerate through isolation and inattention to a detached, alienated group of idealists? Every major and minor social renaissance has had to face this problem.

Hesse’s answer is clear: the last part of the book consists of three tales, allegedly written by Knecht, describing his life in different incarnations. In each one the hero devotes himself wholeheartedly to the service and pursuit of an idealist, spiritual goal, only to recognize at the end that he has become the slave of his own delusions.

In The Indian Life this is clearest: Dasa, the young Brahmin, meets a yogi who asks him to fetch water; by the stream Dasa falls asleep. Later he marries, becomes a prince, has children, wages war, pursues learning, is defeated, hurt, humiliated, imprisoned, dies and—wakes up by the stream in the forest to discover that everything had been an illusion.

"Everything had been displaced in time and everything had been telescoped within the twinkling of an eye: everything was a dream, even that which had seemed dire truth and perhaps also all that which had happened previously—the story of the prince’s son Dasa, his cow-herd’s life, his marriage, his revenge upon Nala and his sojourn with the Yogi. They were all pictures such as one may admire on a carved palace wall, where flowers, stars, birds, apes and gods can be seen portrayed in bas-relief. Was not all that which he had most recently experienced and now had before his eyes—this awakening out of his dream of princehood, war and prison, this standing by the spring, this water bowl which he had just shaken, along with the thoughts he was now thinking—ultimately woven of the same stuff? Was it not dream, illusion, Maya? And what he was about to live in the future, see with his eyes and feel with his hands until death should come — was that of other stuff, of some other fashion? It was a game and a delusion, foam and dream, it was Maya, the whole beautiful, dreadful, enchanting and desperate kaleidoscope of life with its burning joys and sorrows.

The life of Joseph Knecht is described as a series of awakenings from the time he is “called” to enter the Castalian hierarchy (‘Knecht’ in German means ‘servant’, through his period as Magister Ludi, to his eventual renunciation of the order and the game, Castalia is essentially the League, frozen into a social institution.

Again the trickster involves us in his magnificent utopian vision, the “Game of games,” only to show at the end of the transience of this form as of all others. Having reached the highest position possible in the order, Knecht resigns his post. He warns the order of its lack of contact with the outside world and points out that Castalia, like any other social form, is limited in time, In his justificatory speech he refers to “a kind of spiritual experience which I have undergone from time to time and which I call ‘awakening.’"

"I have never thought of these awakenings as manifestations of a God or a demon or even of an absolute truth. What gives them weight and credibility is not their contact with truth, their high origin, their divinity or anything in that nature, but their reality. They are monstrously real in their presence and inescapability, like some violent bodily pain or surprising natural phenomenon... My life, as I saw it, was to be a transcendence, a progress from step to step, a series of realms to be traversed and left behind one after another, just as a piece of music perfects, completes and leaves behind theme after theme, tempo after tempo, never tired, never sleeping, always aware and always perfect in the present. I had noticed that, coincidental with the experience of awakening, there actually were such steps and realms, and that each time a life stage was coming to an end it was fraught with decay and a desire for death before leading to a new realm, and awakening and to a new beginning."

The mystic or visionary is always in opposition to or outside of social institutions, and even if the institution is the most perfect imaginable, the Game of Games, even if it is the one created by oneself, this too is transient, limited, another realm to be traversed. After leaving Castalia, Knecht wanders off on foot:

"It was all perfectly new again, mysterious and of great promise; everything that had once been could be revived, and much that was new besides. It seemed ages since the day and the world had looked so beautiful, innocent and undismayed. The joy of freedom and independence flowed through his veins like a strong potion, and he recalled how long it was since he had left this precious sensation, this lovely and enchanting illusion!”

So there it is. The saga of H.H. The critics tell us that Hesse is the master novelist. Well, maybe. But the novel is a social form, and the social in Hesse is exoteric. At another level, Hesse is the master guide to the psychedelic experience and its application.

Before your LSD session, read Siddhartha and Steppenwolf. The last part of the Steppenwolf is a priceless manual.

Then when you face the problem of integrating your visions with the plastic-doll routine of your life, study Journey to the East.

Find yourself a magic circle. League members await you on all sides. With more psychedelic experience, you will grapple with the problem of language and communication, and your thoughts and your actions will be multiplied in creative complexity as you learn how to play with the interdisciplinary symbols, the multi-level metaphors. The Bead Game.

But always—Hesse reminds us—stay close to the internal core, The mystic formulae, the League, the staggeringly rich intellectual potentials are deadening traps if the internal flame is not kept burning. The flame is of course always there, within and without, surrounding us, keeping us alive. Our only task is to keep tuned in.

Although the argument of the preceding commentary does not depend on the answer to this question, there are sufficient clues in Hesse’s writings to make the matter of some historical and literary interest. In Germany, at the time Hesse was writing, considerable research on mescaline was going on. This has been reported in a monograph by Kurt Beringer, Der Meskalinrausch. Much of the material was also analyzed in Heinrich Kliiver’s monograph, Mescal, the first book on mescaline published in English. (Mescal. The 'divine' Plant and its Psychological Effects. London: Kegan Paul, Trench & Trubner, 1928, (To be reprinted late 1964, Univ. of Chicago Press, )

In response to our inquiry, Professor Kliiver, now at the University of Chicago, has written :

Readers of the Psychedelic Review who have any further information bearing on this question are invited to communicate with the editors.

[2] Steppenwolf. (Transl. Basil Creighton.) New York: Holt (1929); Ungar (1957); Random House [Modern Library] (1963). (Quotes from pp. vi, 62, 63, 66-7, 197-99, 217, 246.) [Der Steppenwolf. Berlin: S. Fischer, 1927.]

[3] The Journey to the East. (Transl. Hilda Rosner.) New York Noonday Press Paperback, 1957. (Quotes from pp. 31, 3, 10, 27-8, 29,118. Translation occasionally amended.) [Die Morgenlandfahrt. Eine Erzahlung. Berlin: S. Fischer, 1932.] Kurt Beringer: Der Meskalinrausch, seine Geschichte und Erscheinungsweise. Berlin: Springer, 1927.

[5] René Daumal: Mount Analogue. An Authentic Narrative. (Transl. and intro by Roger Shattuck; postface by Véra Daumal.) London: Vincent Stuart, 1959. New York: Pantheon, 1960. [Le mont analogue. Préface Dar Rolland de Renéville, récit véridique. Paris: Librairie Gallimard, 1952.]

[6] Bernhard Zeller: Hermann Hesse: Eine Chronik in Bildern. Frankfurt a.M.; Suhrkamp, 1960.

[7] Magister Ludi (The Bead Game). (Transl. Mervyn Savill.) New York: Holt (1949); Ungar Paperback (1957). (Quotes from pp. 17, 39, 10, 500-1, 355-6, 359, 367.) [Das Glasperlenspiel. Versuch einer Lebensbeschreibung des Magister Ludi Josef Knecht samt Knechts hinterlassenen Schriften. 2 vv. Zurich: Fretz & Wasmuth, 1943. Frankfurt a.M.: Suhrkamp, 1961.]

A complete listing of Hesse’s works and the critical literature on him is available in Helmut Waibler’s Hermann Hesse: Eine Bibliographic. Bern und Minchen: Francke, 1962. Pp. 350.

This article originally appeared in Psychedelic Review, Issue Number 2, 1963. It was lovingly transcribed by volunteers at The Castalia Foundation in Millbrook, USA.